This is the first in a series of very brief reviews on some new books in Arabic on Ibāḍī history which have been published by Tunisian presses over the past year. The first book is:

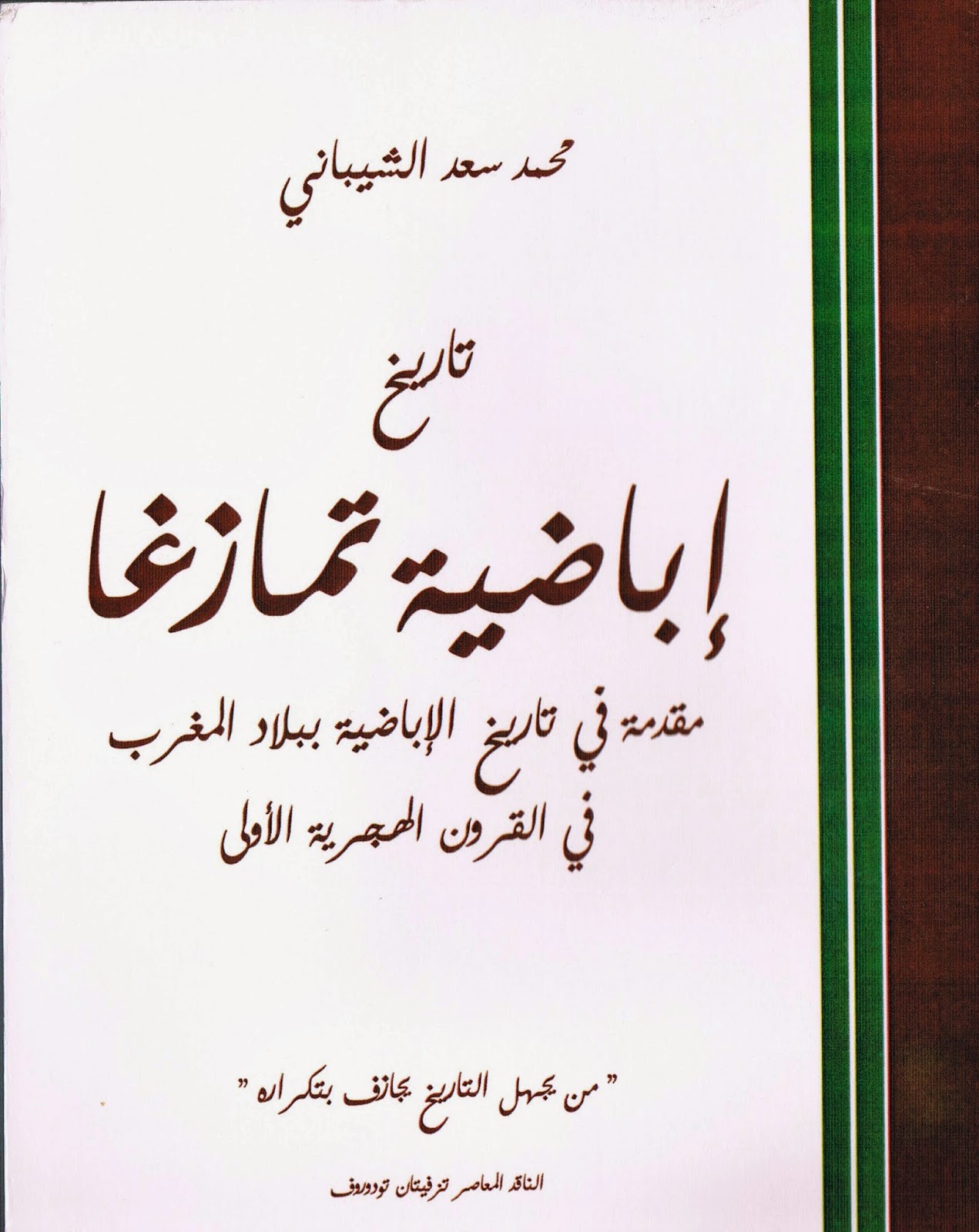

Mohamed Saad Chibani, The History of the Tamazgha Ibadis: An Introduction to the History of the Ibadis in [the] Maghreb in the First Hijri Centuries

محمد سعيد الشيباني

[تاريخ إباضية تمازغا مقدمة ي تاريخ الإباضية ببلاد المغرب في القرون الخجرية الأولى]

This nearly-500 page work stands as a testament to a not-so-new trend in Maghribi historiography to rewrite the history of the Maghrib from what is imagined to be the more or less unified Amazigh perspective. Another part of this trend--which is new in Tunisia--is that the two covers of the book bear the title in Arabic, English, and Tamazight (but not French, curiously).

Chibani addresses the history of the eastern Maghrib both before and after the Arab conquests of the 7th and 8th centuries, emphasizing the distinction between the Arabic-speaking invaders and what he regards as the autochthonous populations of the Maghrib. Lately referred to collectively as Imazighen (s. Amazigh), Chibani uses the term Tamazgha. He offers some etymological analysis of toponyms, onomastic data, and a whole variety of 'Arabic' words that he argues are actually Amazigh words. A central argument of the work is that the Arabs and the autochthonous populations of the Maghrib remained distinct in the early centuries, which he believes is a historical point overlook by mainstream historiography. There were no alliances between these two groups, he argues, only occasional shared interests. Chibani also recycles the nomad/settled divide of earlier historiography on the Maghrib.

The bibliography of the work contains a handful of recent works on Amazigh and Tunisian history in Arabic, which are probably largely unknown to European or American audiences. Unfortunately, the bibliography does not suggest that the author had much interest in addressing historical or historiographical arguments in any European languages.

Although an interesting primary source for the study of a movement in modern Amazigh historiography and a good review of the main highlights of medieval Ibadi history, it must be admitted that the work does not contribute much new information or analysis of what is by now a well-known, traditional version of Ibadi history. Perhaps the distinguishing contribution of this work is Chibani's attempt to recast the history of the Ibadis in the Maghrib as the story of an almost exclusively local phenomenon, rather than simply being introduced from the outside.